Why do most companies get unproductive when they grow?

The Operating System for Evolutionary Organisations - Part 3/10

Foto von Florian Wehde auf Unsplash

The 3 universal principles evolutionary organisations operate by

Why do many companies lose their effectiveness as they expand? Why do so many individuals working in large corporations describe their roles as tedious and sluggish, where decisions and actions seem to drag on and the impact of their efforts often remains unclear? What causes these large corporations to lose their agility, speed, and overall effectiveness? And what do the few evolutionary organisations have in common that make them a more productive and fulfilling workplace while they grow? What are the principles that you have to apply to do it better?

In this article, we will explore the 3 universal principles that these companies have in common. It’s the 3rd article of a series of 10 where I will dive into why traditional organizations are doomed to fail and how a new breed of evolutionary organisations offer a better way forward. These innovative companies prioritize people, continuous development, and embrace complexity. Thus fostering happiness and achieving lasting success. On top of that, I sprinkled in a little bit of science and distilled a framework of 3 universal principles and 8 essential components, with which any CEO or founder can transform their organization into a workplace that thrives.

You will start receiving the articles on a bi-weekly basis right here in your inbox. You can also go to the website to read all articles there.

To address the questions from above, we must first delve into the science of human behaviour and the current realities of the world. I have discovered that evolutionary organisations, whether intentionally or unintentionally, align themselves with these scientific insights. Conversely, most traditional organisations tend to operate in opposition to these scientific principles, which ultimately hampers their effectiveness as they expand. I have distilled these insights into three universal principles that guide these evolutionary organisations. These principles are:

Be complexity-aware: they acknowledge that organisations are complex and act accordingly.

Nurture self-determination: people are intrinsically motivated and capable of self-direction in the right environment.

Act developmental: people’s growth never ends and it is the fuel for successful organisations.

Be Complexity-Aware

Have you ever wondered why humanity has successfully reached the moon, yet companies struggle to outpace their competition in growth? How we can manipulate objects using nanotechnology, but wrestle with improving the performance of a business unit? Or how have we developed surgical robots for intricate procedures, but still grapple with delivering accessible and high-quality healthcare?

Here's the underlying issue. Human beings excel at tackling intricate technical problems by connecting one technical element to another in a linear fashion. However, when confronted with multidimensional challenges, it's an entirely different story. These challenges can't be resolved through linear thinking or solely relying on technical expertise. Sometimes, they evolve and change faster than our ability to respond. They don't wait patiently for solutions; they represent complex problems, distinct from merely complicated ones.

The most significant challenges leaders confront today are inherently complex. They involve tasks such as doubling a company's growth, instigating cultural transformations, providing unparalleled consumer experience, adhering to new regulations, or containing an epidemic. The problem arises when leaders attempt to address these highly complex challenges as if they were merely complicated, and this approach is fundamentally flawed.

Complicated problems are characterised by their intricacy and the presence of many components, but they can often be broken down into manageable parts. These parts interact with one another in predictable ways. These problems have clear cause-and-effect relationships and can be addressed using known processes and expertise. There usually are ready-made solutions to them and they can be fixed with a high degree of confidence, nevertheless, they might still require specialised expertise. Complicated problems are prevalent in fields like engineering, technology and manufacturing.

Examples of complicated problems:

Building a spacecraft: Designing and building a spacecraft involves numerous components and engineering challenges, but each can be addressed through established engineering principles.

Software development: Developing complex software applications may require writing thousands of lines of code, but each part follows predefined coding standards and practices.

Complex problems are also characterised by their intricacy, as well as the presence of multiple interconnected factors. These problems rarely have a single straightforward solution and often involve ambiguity and uncertainty. Complex problems tend to be dynamic, evolving over time, and influenced by a myriad of variables. They require a deep understanding of the underlying dynamics and are often found in fields like sociology, economics and ecology. Complexity is inherently uncertain. We can formulate educated hypotheses about potential developments, yet certainty remains elusive. ”Complex issues cannot be solved but only management.” says Aaron Dignan, organisational expert, in his book “Brave New Work”.

Solving a complex problem demands a “tortoise-and-hare” hybrid approach. This means pausing to understand what’s happening, thinking it through, deciding on a new course of action, and getting going again. It requires system thinking (to understand the underlying systems and relationships), interdisciplinary collaboration, continuous learning, experimentation and engagement with all stakeholders. 1

Therefore, you can’t plan everything and have to stay agile and flexible in the ever-changing business world of today. Ideally, this would mean that you need to become antifragile, as described by writer Nassim Taleb in his famous book “Antifragile: Things That Gain from Disorder”. According to the author, being antifragile is a skill that allows an individual to react to stress differently and thrive from shocks and volatility, which is how one can stay afloat in the context of complexity.

Let’s have a look at the way traffic works to better understand how to solve complex problems. Traffic is complex because it’s influenced by many factors and cannot be easily controlled or dissolved at will.

Dignan provides a great example in his book on how to manage problems considered to be complex, like traffic:

The traffic light way: not trusting the stakeholders, solving complex problems with a lot of elaborate rules/technology for every scenario.

The roundabout way: trusting the stakeholders, solving complex problems with simple rules and agreement between all participants of the process.

As we can see from these simple explanations, the roundabout way is obviously easier, cheaper to build and overall more effective. When building organisations using the roundabout way, it reaps better results.

The traffic light way, on the other hand, is harder to set up, as you need to set up traffic lights, lay electricity, as well as understand the traffic flow and how it changes over time to configure it correctly. It then somewhat solves the problem, but not really well and at a higher cost. Who has not been in long waiting lines on one side of the traffic light, for example, when you want to turn left, and all other roads of the junction were almost empty? Or a broken traffic light that requires police to come and intervene. But have you ever seen a roundabout not working?

It’s similar when you think about an organisation. There are so many moving parts within your organisation, not even including all the things happening on the market at any given moment. You can impossibly plan all possible scenarios beforehand. You can also try to set up policies to mitigate the risk of misbehaviour of employees, but you will notice that you will be blocking some people and still forget to cover other topics that then will go wrong. So, instead, you should trust your people and provide them with some high-level guidance or rules — the roundabout way. At the companies that I built, we also implemented this tactic by trusting our people and setting simple basic rules and values. It works like magic. Less overhead, more productivity and happier people as they get more autonomy.

It’s also similar to a city that gets more and more productive the more people move there. Not like a huge corporate entity. Ever seen things happening fast in these? They seem more like an overweight freighter that’s drowning. On the contrary, in a city, there are only very few rules. Most is left to the inhabitants.

Nurture Self-Determination

Much of what we know about motivation is wrong: people don’t need carrots and sticks. The self-determination theory reveals that people are intrinsically motivated if the right conditions are met. So, if you put people in the right place, they will drive change intrinsically and give their best.

The dominant view, the one held by ordinary organisations, paints a mechanical picture of who we are — people conditioned by basic rewards and punishments, with our future inevitably dictated by our past experiences. Such a mindset assumes that we are not interested in working or learning without an incentive to do so. Hence, these organisations believe that their employees must be coerced and controlled, both within the organisations and in the general social context. But the carrot-and-stick approach to motivation is flawed.

As humans, we have an innate desire to realise our full potential and achieve our goals.

Researchers Edward L. Deci and Richard M. Ryan proved this with their self-determination theory (SDT) and suggested that people are naturally motivated and capable of self-direction.

The theory states that people are motivated to grow and change by three innate (and universal) psychological needs:

Competence: People need to gain mastery of tasks and learn different skills.

Autonomy: People need to feel in control of their own behaviours and goals.

Relatedness: People need to experience a sense of belonging and attachment to other people.

Daniel Pink builds upon that theory in his book “Drive” and explores how to best motivate people. Research shows that the secret to high performance isn’t our biological drive or our reward-and-punishment drive, but our third drive — our deep-seated desire to direct our own lives, extend and expand our abilities and live a life of purpose.

If we look at the different types of work someone can do, there is two types that can be outlined clearly:

Algorithmic: you pretty much do the same thing over and over in a certain way, or;

Heuristic: you have to come up with something new every time because there are no set instructions to follow.

If you do the same things over and over, which means algorithmic work, then the carrot-and-stick approach actually works. There is no need for intrinsic motivation. The people who get a higher commission for each completed task will work faster and more. But if your work requires more heuristic and creative thinking, like most of the tasks a knowledge worker does nowadays, then a performance-related bonus or reward has the reverse effect and reduces intrinsic motivation.

Deci showed so in a study in 1971, where participants were tasked to solve puzzles. The group that was given rewards lost interest in solving them as soon as they stopped getting rewards. Whereas, the other group that never got any rewards, kept solving the puzzles and even continued to do so for a longer period of time, becoming even more engaged from round to round. “When money is used as an external reward for some activity, the subjects lose intrinsic interest in the activity”, — the researcher concluded. This was controversial at that time and still is to many because no one expected that rewards would have negative effects on motivation.2

Pink therefore proposes a new approach to creating intrinsic motivation in anyone, away from monetary rewards and focused on three essential elements:

Autonomy: the desire to direct our own lives;

Mastery: the urge to get better and better at something that matters;

Purpose: the yearning to do what we do in the service of something larger than ourselves.

Therefore, if you set the stage right for your employees by trusting them with autonomy, allowing them to grow and making their work meaningful, their inner motivation will thrive by itself.

Act Developmental

Adult development does not stop but goes on continuously through 5 total stages of development. Employees operating at the last stage are far more effective. Organisations that have understood this outperform the others. They create an environment where people can flourish.

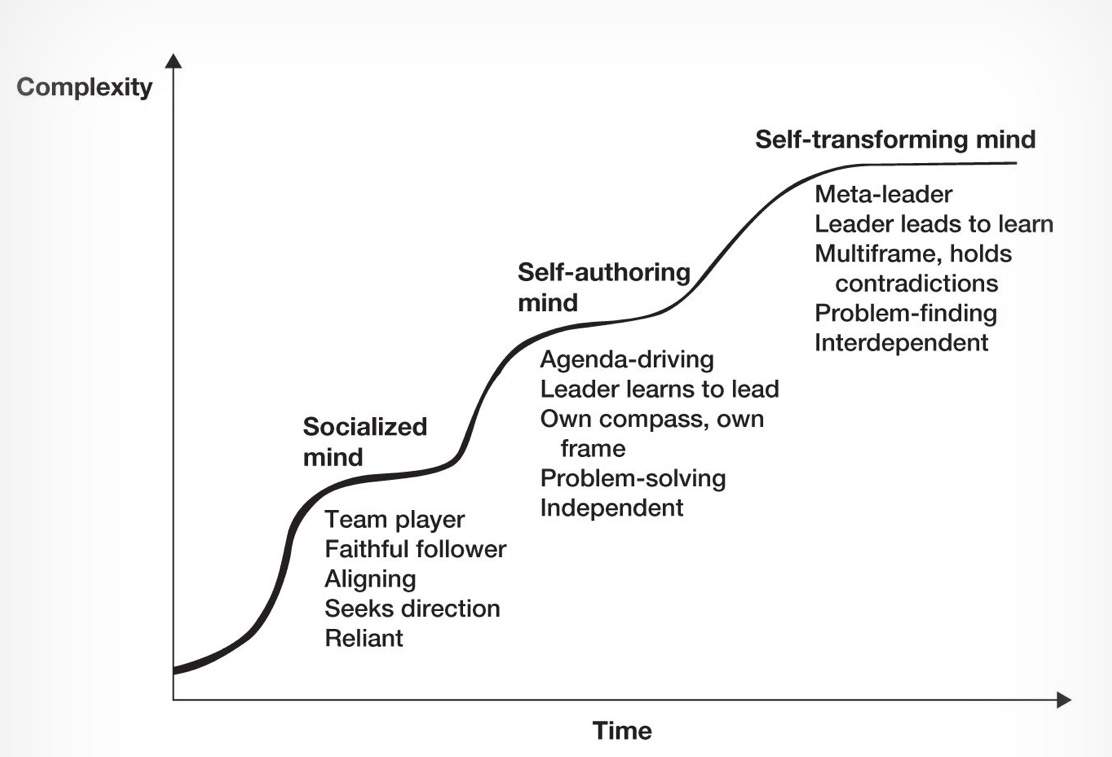

Psychologists previously thought that adult development stops at the age of 18. Instead, recent research by Robert Kegan and Lisa Lahey (more in their book “An everyone culture: Deliberately Developmental Organisations (DDO)”), shows that adult development happens at various stages, each representing a different way of knowing the world. (See Fig. 2-2).

In total, there are five stages but here (see picture below) we will focus on the last three, which are the most relevant for adults. (See summaries of part1, part2, part3)

In the diagram below (see Fig. 2-5), we can see a clear upward slope, signifying that increased mental complexity and work competence, assessed on a number of dimensions, are correlated. Thus, not only is it possible to reach higher planes of mental complexity, but such growth will also be correlated with effectiveness for both CEOs and middle managers. These findings have been replicated in a variety of fine-grained studies on small numbers of leaders, assessed on their particular competencies.

In the past, it was enough for individuals at work to be good team players and demonstrate loyalty to the organisation. Employees like this were considered reliable and were expected to carefully follow the directions and instructions given out by their boss. All of these are the characteristics of a mindset we call a “socialised mind”. In other words, the socialised mind would be perfectly adequate to handle the nature of yesterday’s demands from employees — but, today, things have changed.

The transformation from a manufacturing to an information society has set these changes into motion. At the same time, the concept of a “self-authoring mind” is something that is gradually becoming more and more valuable for evolutionary organisations. A self-authoring mind is characterised by independence, self-trust and confidence in solving problems. A person who has a self-authoring mind is someone who is able to step back from the outside environment to form their own judgment, as well as is capable of self-direction and regulation of their own boundaries.

In turn, a self-transforming mind is characterised by the individual’s ability to step back and reflect on their own thinking limitations and implement ways to overcome these. It can hold multiple systems of thinking and ideology rather than projecting all into one and it is friendlier towards contradiction and opposing views.

Organisations today increasingly need a higher level of knowledge and skills from their employees, who are also expected to be autonomous in their decision-making, as well as self-reliant and internally motivated.

Moreover, the pressure is even higher for the new generation of leaders. These new leaders should be able to step outside their own ideology, observe its limitations and defects, as well as be able to come up with a more comprehensive view — the one that holds sufficient tentativeness to discover its limitations as well. In other words, this kind of leader needs to be a person who is creating meaning with a self-transforming mind.

Therefore, organisations are asking workers who once performed their work successfully with socialised minds, being good soldiers, to make a shift to a self-authoring mind. In addition, organisations want leaders who once led successfully with self-authoring minds, being sure and certain captains, to develop self-transforming minds. In short, organisations expect a quantum shift in individuals’ mental complexity across the board.

To summarise:

Development is a specific, describable and detectable phenomenon. It is the growth of our mindsets, meaning-making logic and qualitative advances in our abilities to see more deeply and accurately into ourselves and our worlds. It is the process of successively being able to look at the premises and assumptions we formerly looked through.

Development has a robust scientific foundation. This was demonstrated after 40 years of research by investigators across the world, with a wide diversity of samples and reliable means of measurement.

Development has a business value. Organisations need more employees in possession of the more complex mindsets, and this need will intensify in the years ahead.

In the book “Principles” Ray Dalio, uses a helpful analogy that also works well to illustrate this concept further: to think about actions of the mind as a set of outcomes produced by a machine. Then you can understand how the input, your upstream actions, result in an output, downstream. This way, you can practice higher-level thinking by looking down on your machine and thinking about how it can be changed to produce better outcomes.

Let’s have a look at an employee called Sergio who is a self-identified people-pleaser. He creates a suboptimal set of slides. To understand the mechanisms of why this happened, we need to understand what happened upstream (Sergio’s actions) in order to determine how it affected the result downstream (low quality of the slides). To determine the cause (upstream) and effect (set of slides), we need to answer the question: why did people-pleaser Sergio produce a suboptimal set of slides? The answer is that Sergio, being a people-pleaser, did not want to bother his colleagues with too many questions and ask them for feedback to avoid negative comments. Hence, this led to a low quality of his work. The conclusion we can draw from this example is simple: what you do upstream affects what you get downstream. Therefore, to prevent negative outcomes, you need to pay attention to what causes them in the first place.

Here, Sergio acted from the position of a socialised mind. If he were to act from the position of a self-authoring mind, he would take into account his desire to please people as an obstacle to creating a good set of slides. This would also have allowed him not only to understand himself better but, using this information, to take the necessary action not to allow his people-pleasing tendencies to get in the way.

Moreover, having a self-transforming mind, he would be able to question his people-pleasing tendencies, address the underlying beliefs and then change his belief system in a suitable and appropriate way. Then, he doesn’t have to work with those tendencies that get in his way and instead get rid of them.

Evolutionary organisations are companies that consistently apply this developmental principle in their work, encouraging a self-authoring mind over a socialised mind, challenging their employees to come up with creative solutions and pushing them to learn constantly. They challenge their employees by putting them in new roles as soon as they have mastered the responsibilities in their previous role and they stir things up to help their workers learn.

All evolutionary organisations acknowledge these three universal principles. They chose to solve a problem the roundabout way by tackling the complex task of building and leading an organisation to success with few simple, dynamic and agile rules. They stay flexible to adapt to changing conditions. They trust people and set the right conditions to develop their inner drive and develop each and every one to their fullest potential. On top of these guiding principles, we developed an operating system that will allow you to transform your organisation into an evolutionary one.

In the next article, I will dive in one step deeper and explain the operating system of the future. If you are interested, please subscribe. I will then notify you when I release the 4th article (in around 2 weeks) and send you the full white paper about the operating system for evolutionary organizations when it’s done.

David Komlos and David Benjamin authors of the book “Cracking Complexity: The Breakthrough Formula for Solving Just About Anything fast”

Edward L. Deci, “Effects of Externally Mediated Rewards on Intrinsic Motivation,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 18 (1971): 114